Knit Basics

What Are Knits?

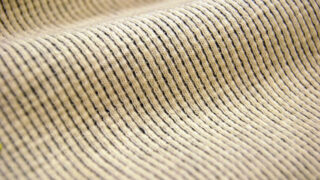

Knits are made by intermeshing yarn into loops to form a fabric. Compared with woven constructions, which are rigid and stable, knits easily conform to the human body. The intermeshed loops of knits allow for flexibility as they stretch to fit the form. This mobility helps knitted fabrics maintain a smoother appearance than woven fabrics, making knitted apparel well-suited for sports and other active endeavors.

Common apparel items in the knit classifications are t-shirts, polos, sweaters, hoodies, joggers, and active garments like tights, leggings, sports bras, and fleece. Knits have a sizeable aesthetic range from casual to high-end luxury, depending on the yarn, fabric, and finish.

Knit garments have a tremendous range in texture due to the ability to mix yarns and play with knit stitch structures. Due to the natural stretch in most knit fabrics, knit garments are best suited when there is a need for stretch, movement, or comfort.

In this section, you will learn the basics of knit fundamentals, from the three knit stitches (knit, tuck, and float), to the various weft and warp knitting machines and their capabilities.

History of Knitting

Knitting is one of the earliest methods devised to form yarn into fabric and garments. Evidence of techniques and various materials, including cotton, traces back to 1000 B.C. with the origin of knitting suggested by historian Richard Rutt to have been in Egypt. The knitted stockings from Egypt dating back to approximately the 12th century already show a complexity in techniques that suggests knitting had existed for some time even before these stockings.

Knitting became more common in the 15th century when it spread throughout Europe. Worn for comfort and style, hand-knitted fabrics became so popular that by 1488, the British Parliament controlled the price of knitted caps. Henry VIII was the first monarch to wear fitted knit stockings instead of loose trousers, and Queen Elizabeth I, who preferred stockings knit of silk, encouraged the formation of knitting guilds in England.

To increase production, in 1589, a British gentleman named William Lee invented the first mechanical knitting frame. The original machine only had 8 needles per inch and was later improved to 20 needles per inch to knit stockings in silk and wool. Its development and use created a commercial industry around knit products like hosiery and legwear. By the mid-19th century, improvements in steam-powered knitting machines transitioned production to factories to accommodate larger machinery and production volume. In the 21st century, knitting has seen a resurgence in manufacturing capabilities and as a DIY craft movement.

Engraving of an 1800’s knitting machine

Advancements in yarn quality driven by global sourcing and trading, coupled with technological innovations in manufacturing machinery, have improved the possibilities for knit products in the fashion industry. Knit garments have become staples in modern wardrobes, catering to diverse lifestyle needs such as activewear supporting movement and recovery, casualwear emphasizing comfort and durability, and dresswear demanding elegance and simplicity. Knits are unsurpassed in their broad range of styles and applications.

Knit Properties

To understand knits, we must first learn the basic structure that differentiates knits from wovens.

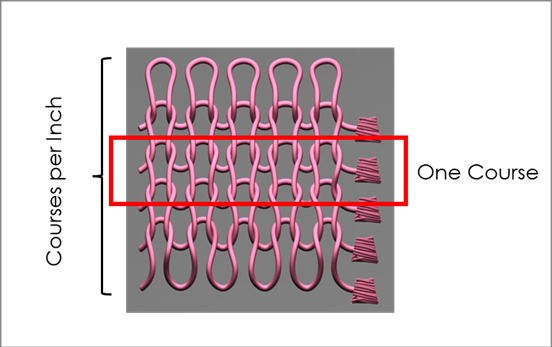

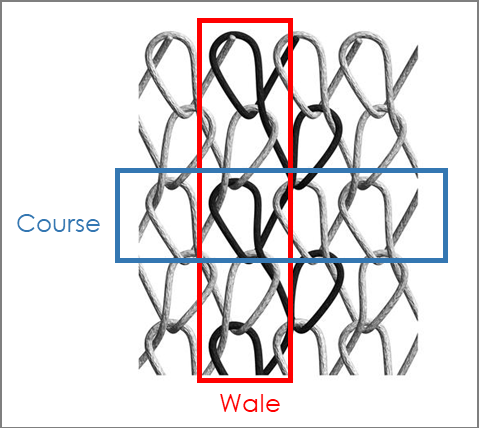

Knit loops are formed by needles knitting across the width of the fabric in a horizontal direction. This is called the course. In the first illustration, if the square is one inch, the swatch has five courses per inch.

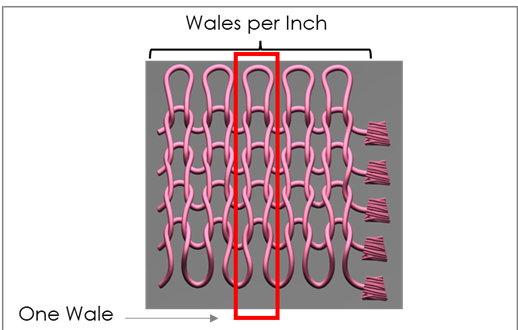

When we look at the same swatch and refer to the vertical column of loops, this is called the wale. In the second illustration, there are five wales per inch.

When we look at a single jersey stitch, the stitch breaks down into two elements: the crown and the legs . You will notice that the legs form a “v” shape, and the crown is more noticeable on the reverse side of the fabric. Learning to find the crown and legs leads to understanding stitch count and gauge.

All knits are composed of a variation of three core stitches: knit (jersey), tuck, and float.

Knit Stitch

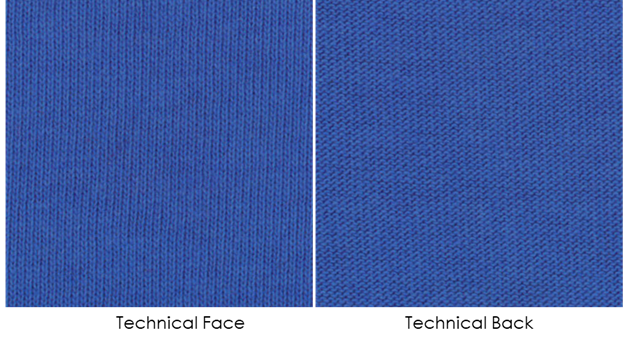

The knit stitch is also referred to as the technical face. The fabric is called a single jersey if every needle is fed a yarn and goes through the basic knitting cycle. All loops use the knit stitch, and all loops look precisely alike.

The length of yarn in that loop is called the stitch length. Each loop has legs and a crown. Referred to as a jersey stitch, stitches arranged in this pattern have a distinctly different look and feel from the face to the back.

On the technical face side, the stitches have an overall vertical appearance, and you see primarily the legs. On the technical back side, the stitches have an overall horizontal appearance, and you see mainly the crowns.

Tuck Stitch

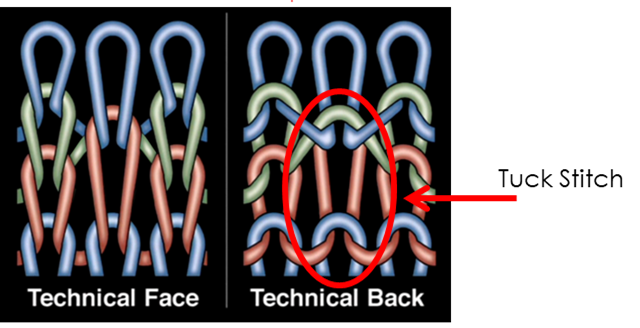

The tuck stitch gets its name from one yarn tucking behind the others and hiding. Follow the green shaded course of yarn across the pattern, and it looks like a loop has been tucked behind another.

The pattern on the right shows the technical back for a tuck stitch. From the back, the tuck is more visible. Depending on the type of tuck stitch, it usually creates a hole in the fabric.

Tuck stitches can give the fabric a cellular appearance. Some people refer to this as mesh. Tucks are the basis for pique fabrics typically used for golf and tennis shirts that need to breathe and retain their shape but have stretch and breathability. A wide range of pique constructions can be made, depending on the use and frequency of tuck stitches.

How is a tuck stitch made?

During the tuck cycle, at feed one, the needle moves up from its rest position, and the old stitch that has been formed is held and not allowed to clear the latch. The needle then moves up far enough to grab a second yarn, which is put into a tuck position. Both yarns are then kept at the rest position. The knitting cycle occurs with the next feed of yarn. At this time, both yarns are cleared. The new yarn is fed and pulled through the held and tuck loops, forming a tuck stitch. The stress caused by holding one elongated stitch for an extra course causes more length shrinkage and less in the width of a regular knitted stitch. The tuck loop makes the fabric wider, thicker, and slightly less extensible.

Float Stitch

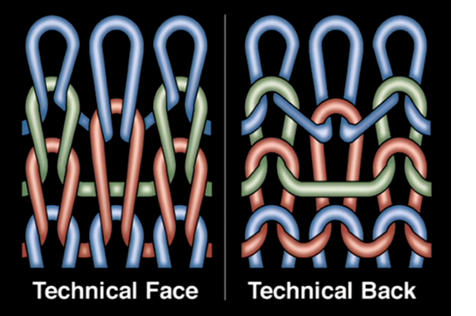

The float stitch comprises of a held loop and one or more float loops. It results when a needle still holding its old loop receives no new yarn. Instead, the new yarn passes as a float loop to the back of the needle and held loop. This is also called a miss, skip, or slip stitch.

To produce the float stitch, one feed yarn is laid to rest behind the hook of the needle. The needle remains in the rest position in the float cycle. In the knitting cycle, it is activated. When a subsequent yarn is knit at the next feed, the missed yarn floats to the technical back of the fabric.

Loops can be made to float over a series of wales. To secure the structure, some float yarns can be tied to the ground with a jersey or tuck stitch. Float loops make the fabric more narrow and less extensible because the floated yarn is in a straight configuration. Why would you produce a structure with loops that float? Floats are useful for pattern effects where some colors appear on the front, and others are hidden on the back. This houndstooth pattern uses red and black yarns. When the red yarn knits a red houndstooth on the front, the black yarn floats to the back.

If you turn the fabric over and inspect the back, the colors appear reversed. A second use is to create surface effects or change the performance of the fabric. You can make loops float on one side of the fabric, then nap them to produce a fleece. If not napped, these floats could be used for aesthetics or function.

All three of these stitch formations can be produced with warp and weft knitting and single or double-knit machines.

Stitch Length

The final term to know when understanding the basics of knit stitches is the stitch length. The amount of yarn in one stitch in inches or centimeters (course length divided by the number of needles used) is the stitch length. Adjusting the stitch length controls the tension of the knit fabric. Shortening the stitch length will create a tighter tension, and lengthening the stitch length will create a looser fabric.

Yarn Prep

During knitting, yarns are under low tension levels and thus require a lower twist. The yarns feed from individual packages and thread independently. Multiple knitting needles pick up each yarn, creating high yarn-to-metal abrasion. Waxing the yarn reduces this abrasion and provides consistent yarn tension levels. Knitted fabrics require finishing to remove the wax coating from the yarns.

Weft Knitting

Weft knitting is accomplished by loops forming in a horizontal manner across the width of the fabric by adjacent needles. Characteristics of weft knit fabrics are that they have more of a horizontal stretch, and the fabric curls, runs, and unravels at both ends.

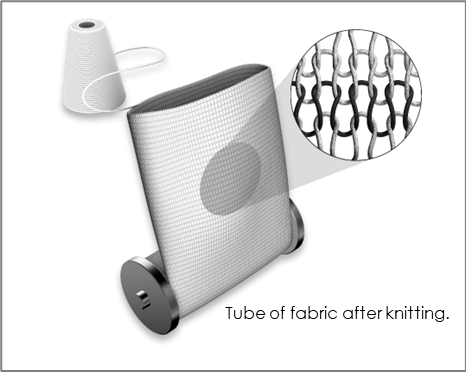

The most common machine used for weft knitting is the circular knitting machine. The circular knitting machine creates a fabric tube in a spiral configuration around a cylinder.

The number of needles on the machine determines the width of the fabric. One revolution of the machine completes one coarse for each yarn fed.

Circular weft knitting machine

Circular weft knitting machines knit in horizontal courses, and the fabric produced is a continuous tube.

The second type of weft knitting machine is a flat-bed machine. With a flat-bed machine, the needles are arranged in a straight line on a flat plate called the bed. These machines may have only one bed of needles or two beds opposite each other. It is commonly used to produce sweaters, trims, scarves, and similar fabrics.

Regardless of the type of machine used, in weft knitting, needles placed next to each other knit one after another in sequence to produce one row of loops from the same yarn.

Warp Knitting

Warp knitting, in contrast to weft knitting, is accomplished by forming loops in a vertical direction. Looking closely at the illustration of the warp knit, you see that the yarn is intermeshed vertically with two wales.

A warp knitting machine creates each individual loop from separate lengthwise yarns. Wound onto a beam from yarn packages in a creel, the yarns arranged as a warp must be placed parallel to each other. Normally, for the most basic fabrics, each yarn needs its own needle. If one thousand needles are used on this machine, there needs to be a minimum of one thousand warp yarns.

A typical Warp Knitting Machine

If there is more than one yarn provided for each needle, more elaborate fabrics can be produced.

With warp knitting, individual needles knit simultaneously across the width of the machine. Loops are formed by needles knitting a series of warp yarns fed vertically and parallel to the direction of the fabric formation. Warp-knitted fabrics have different properties than weft knits. They have more of a vertical stretch, which makes warp knits great for swim and active garments. Warp knits can be very fine making them suitable for hosiery and intimates. They also do not fray or curl at the end if cut horizontally. Warp knitting machines typically produce tricot, raschel, and crochet fabrics

Warp knit machines take a long time to set up and run at high speeds. All the needles run simultaneously compared to weft knitting, where the needles run in sequence. Warp knits are great for high-volume products.